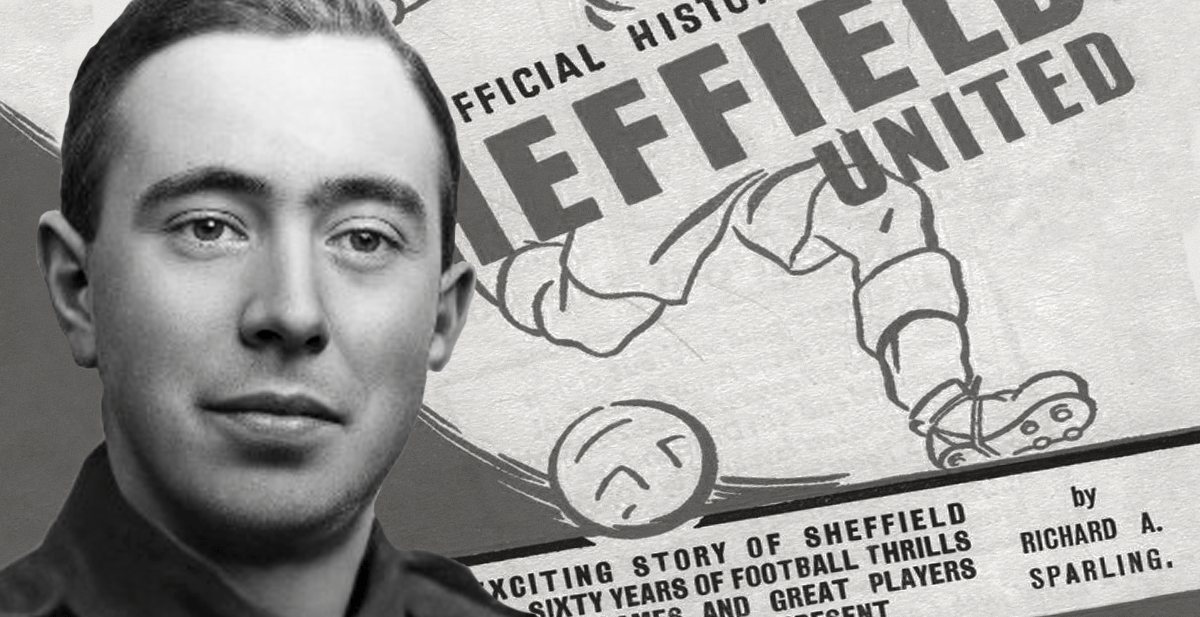

RICHARD SPARLING - SPORTS WRITER AND SOLDIER

In 1926 Richard A. Sparling wrote what was probably the first ever football club history, entitled The Romance of the Wednesday. But this was not his first publication. In 1920 he had written, with the assistance of his fellow sportswriter Howard R. Sleigh, the official history the 12th (Service) Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment. It was a book based on personal experiences as in 1914 they had volunteered with their colleague Herve A. Giraud in response to Lord Kitchener’s famous call for recruits for the army.

Often referred to as the ‘Pals’, these units allowed men from the same area or social class to serve together and the Sheffield City Battalion was a very middle-class unit. The formation was first proposed by two Sheffield University students and the original title of the unit was the Sheffield University and City Special Battalion. Sparling described the type of recruits who joined up:

‘Standing there as privates were many men whom no other conceivable circumstances would have brought into the army; £500 a year business men, University and public school men, medical students, journalists, schoolmasters, craftsmen, shop assistants, secretaries and all sorts of clerks.’

The also attracted a range of the city’s sports stars. The first man to join up was Vivian Simpson, an amateur with Sheffield Wednesday and who later became their captain (Simpson once scored a hat-trick in a 6-0 win against Manchester United). Also serving with the was P. Doncaster from Sheffield United reserves. Twenty-four-year-old Sparling and his colleagues found themselves in D Company but due to their journalistic and administrative skills, Sparling and Sleigh were soon appointed to the Battalion Orderly Staff. The did its training in the Sheffield area and at one time used Bramall Lane to practise drill. Before they left England, Herve Giraud became the first man in the unit to marry, with his platoon buying him a set of smoking pipes and a cross for his wife in recognition of her courage. Sparling himself would marry wife, Millie Archer, on leave in August 1915.

The first went to Egypt but their first major action was the opening day of the Somme on 1 July 1916. As part of 94th Brigade, the Sheffield City Battalion would serve alongside the Accrington Pals and the two s of Barnsley Pals. During training, the Barnsley Pals had been amused by the gramophones and records that the wealthier Sheffield men had brought along and had nicknamed them the ‘coffee and buns boys.’ The objective for 94th Brigade on 1 July 1916 was the village of Serre. Looking back in 1920 Sparling described the attack in pained terms that are worth quoting at length.

‘The 1st of July, 1916, will be remembered as one of the saddest and most tragic, yet withal one of the most glorious pages of Sheffield history, for on that day there fell in battle the largest number of Sheffield men ever known. Around it sacred memories will ever cling as citizens recall the gallant men who in a few minutes put to the test their long months of training.

July 1st will be indelible words in every Englishman’s mind and keywords to almost incomprehensible thoughts and scenes. The man who was present at the battle for Serre will at their mention see again the day before the battle – the toilsome journey through the trenches, half-full of water; see again the tired slumberers of the dawn, the beautiful summer morn, the faultless parade on the parapets, and the unwavering quick march into the hail of bullets and shells; see again those brave comrades mowed down as grass before the scythe, and those odd parties crossing the German trenches, alas! never to return.

He will see again the lightening shell-bursts, hear their stunning crashes and feel the shaking of tortured earth. He will recall the mangled, blackened bodies and hear the groans of ghastly wounded and voices of grey-faced soldiers as they said to themselves “Let us hush this cry of ‘Forward’ till one thousand years have gone.”

As his thoughts travel he will clench his fists at the recollections of the enemy riflemen sniping the wounded who showed any signs of life, and making target practise of the dead. He will feel again the burning ray of the brilliant midday sun, and see on every hand in dreadful No Man’s Land those glittering triangles, every triangle a symbol of dead, dying and wounded. He will think of the parched lip and throat, and hearts of anguish, pain, and suffering, and then of the welcome sunset and more welcome shades of night, which enabled the living and hysterical wounded to reach our lines, some by crawling, some by crouching runs, and some by painful dragging of bodies…

This is a jumbled, vague story which has been told. But no clear narrative seems possible. The record consists merely of fragments picked up and pieced together: from what the men tell me of their little bits of the battle, from what one saw through the waving July grass on a trench top, from what the observers and airmen saw in the brief glimpses through the murky cloud of dust and smoke. In the regimental records there is a long list of well-remembered men with nothing but the word “missing” marked against them. They went, and they did not come back. That is all. It is so different from one’s dreams.’

The brigade was one of the worst hit. The Sheffield Pals suffered 496 casualties in total, including 8 officers and 240 men killed. The was subsequently reinforced and would later see action during the Battle of Arras in 1917. In 1918 they fought at St Quentin and Bapaume before moving north to counter the German Spring Offensive. The Sheffield City Battalion was eventually disbanded in 1918 as part of army reorganisation.

Both Sparling and Sleigh survived the war but Giraud was killed on 7 May 1917, possibly with the 10th Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment. Sparling and Sleigh were both awarded decorations during the war and the Sheffield Green’Un proudly printed their photographs. Sparling was awarded the Military Service Medal in 1918 whilst Sleigh was awarded the same medal in 1918 and mentioned in dispatches in 1917. Sheffield Wednesday’s Vivian Simpson was awarded the Military Cross in 1917 for planning and leading a successful attack on an enemy trench, being the first man in it and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. Simpson was later killed whilst serving with the Barnsley pals in April 1918.

Sparling and Sleigh both returned to the Sheffield Green’Un and became in turn its editors, Sleigh in the 1930s and Sparling in the 1940s.

In the 1950s and 1960s journalist Richard Harris was inspired by talking to older men at the Sheffield Telegraph to write a novel thinly disguised about the Sheffield City Battalion called Covenant of Death (1961). One wonders whether Richard Sparling was one of the men he spoke to. Harris’ novel concluded with the attack of 1 July 1916. In his memorable words of his narrator, the unit was “Two years in the making. Ten minutes in the destroying. That was our history.”

Dr Alex Jackson

National Football Museum