THE STORY OF DONALD SIMPSON BELL VC

When the British Army launched its great Somme offensive in the summer of 1916, few people could have envisaged the devastation battle would bring. The opening day alone saw British casualties of almost 60,000 and by the time the slaughter had ground to a bloody halt in the November mud, Britain and her dominions had lost a staggering 400,000 men. Among the dead was 25-year-old Donald Simpson Bell, a second lieutenant in the Green Howards who was the only English professional footballer to receive his country’s highest military award for gallantry, the Victoria Cross.

Born in the North Yorkshire town of Harrogate in 1890, Bell attended the local grammar school as a child and it was here that he first came to prominence as a talented sportsman. A keen cricketer, Bell was captain of his school side and it is said he had the attributes to go further in the sport had he wished.

Football was Bell’s first love, however, and a move to London’s Westminster College in September 1909 saw him sign amateur forms with Southern League side Crystal Palace. Despite establishing himself as a regular in the college football team, in addition to its rugby and cricket XI, Bell would leave London on completion of his studies in 1911 having made no appearances for Palace.

Bell subsequently returned to Harrogate where he got a job teaching English at Starbeck School. Nevertheless, football continued to occupy a significant part of Bell’s life and after brief spells with Newcastle United’s reserve side and Bishop Auckland, Bell joined Mirfield United. In October 1912, the 22-year-old earned his first professional contract when he signed terms with Football League Second Division outfit, Bradford Park Avenue.

Comfortable in both defence and midfield, Bell made his Bradford debut against Wolverhampton Wanderers in 1913 and went on to make five more appearances for the club as he helped them secure promotion to the English top flight. Events further afield were now about to impact on both Donald Bell and the country as a whole, however, as Europe was plunged into bloody conflict in August 1914. With a promising footballing career ahead of him, Bell instead asked Avenue to release him from his contract so he could answer Lord Kitchener’s call to arms. This was duly agreed and he enlisted as a private in the 9th (Service) Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment in November 1914.

Bell excelled in military service and was granted a commission with the Yorkshire Regiment, also known as the Green Howards, in the summer of 1915. By the end of that year, the British Army had suffered debilitating casualty figures and Kitchener’s “new army” of volunteers, Second-Lieutenant Bell among them, were being sent across the channel to prepare for the great summer offensive Field Marshall Douglas Haig had planned north of the Somme valley. Bell joined the 9th Green Howards in France and spent time in a relatively quiet sector of the line near Armentieres, before heading south to begin preparations for the upcoming battle.

The opening day of the Battle of the Somme saw the 9th Green Howards placed in reserve near the town of Albert, however, they were soon thrown into the maelstrom when they attacked a portion of the German lines called Horseshoe Trench on 5 July. It was after this action that Donald Bell was recommended for the Victoria Cross. As the Green Howards made their way towards their objective, they immediately came under heavy German machine gun fire from their flank. With the advancing infantry caught in the open, Bell traversed down a communication trench with a junior NCO and a private and destroyed the post with small arms fire and mills bombs. The three men then proceeded to clear a number of enemy dug-outs.

The opening day of the Battle of the Somme saw the 9th Green Howards placed in reserve near the town of Albert, however, they were soon thrown into the maelstrom when they attacked a portion of the German lines called Horseshoe Trench on 5 July. It was after this action that Donald Bell was recommended for the Victoria Cross. As the Green Howards made their way towards their objective, they immediately came under heavy German machine gun fire from their flank. With the advancing infantry caught in the open, Bell traversed down a communication trench with a junior NCO and a private and destroyed the post with small arms fire and mills bombs. The three men then proceeded to clear a number of enemy dug-outs.

Bell’s bravery allowed his battalion to eventually capture their objective and also saved the lives of many of his men. Bell was a reluctant hero, however, and sent a letter to his mother soon after the action in which he wrote: ‘I must confess that it was the biggest fluke alive and I did nothing… I chucked the bomb and it did the trick.’ If it was luck, Bell’s share finally deserted him on 10 July during a similar attack on a German position. Undertaking a bombing attack at the southern end of the village of Contalmaison, the 25-year-old was cut down and died where he fell. His body was later buried by his men and a wooden cross erected in his memory at a position soon to become known as Bell’s Redoubt.

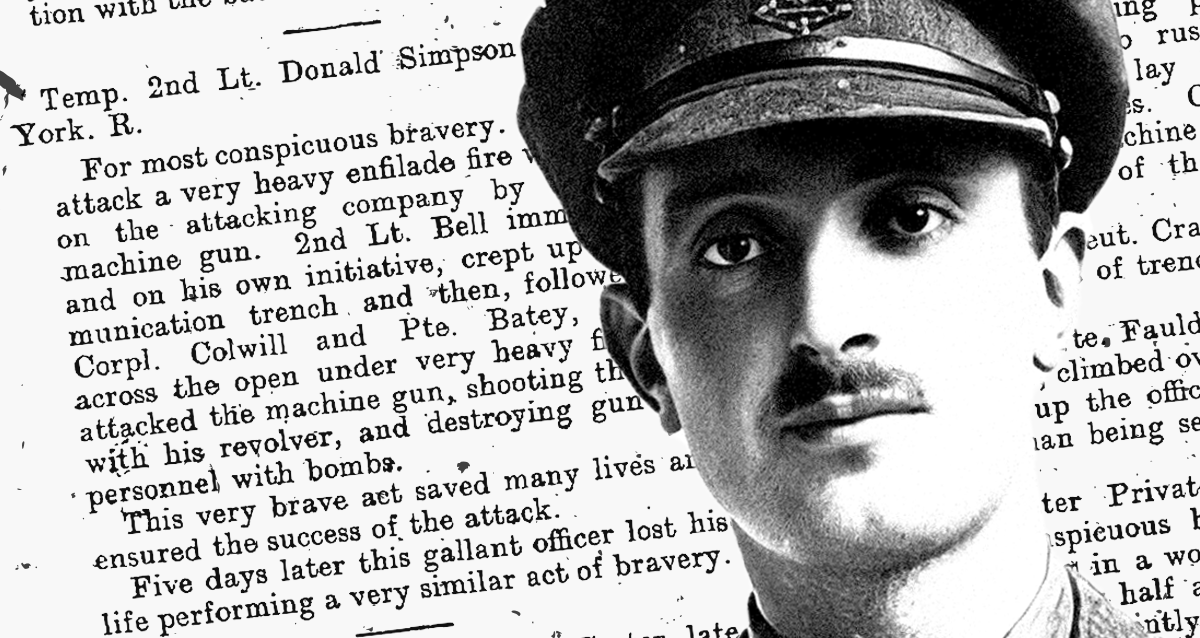

Just weeks after his death, news came through that 2nd Lt Bell had been awarded the British Army’s highest decoration for gallantry after his actions at Horseshoe Trench on 5 July. The awarding of the Victoria Cross was officially announced in the London Gazette on 9 September 1916 and read:

For most conspicuous bravery (Horseshoe Trench, France). During an attack a very heavy enfilade fire was opened on the attacking company by a hostile machine-gun. Lieutenant Bell immediately, and on his own initiative, crept up a communication trench and then, followed by Corporal Colwill and Private Batey, rushed across the open under heavy fire and attacked the machine gun, shooting the firer with his revolver, and destroying gun and personnel with bombs. This very brave act saved many lives and ensured the success of the attack. Five days later this gallant officer lost his life performing a similar act of bravery.

The medal was presented to Bell’s wife Rhoda, who he had married just weeks before his death, in a private ceremony at Buckingham Palace five months later by King George V. After the war, Bell’s body was moved from its initial resting place and reinterred at Gordon Dump Cemetery located in the valley below Ovillers-La Boisselle. In 2000, a memorial sponsored by the Players Football Association (PFA) was erected on the site of Bell’s Redoubt to commemorate the actions of Donald Bell in 1916. Almost one decade later, the PFA also bought his Victoria Cross and campaign medals at auction for a price of £221,000. They are now on display at the National Football Museum in Manchester.