THE STORY OF JIMMY REVILL

Like many professional footballers, deprived of their chief source of earning a living and under pressure to serve their country in its time of crisis, Jimmy Revill enlisted in His Majesty’s forces during World War One. After serving in the army for just over a year, he was killed in action in April 1917; he was the only Sheffield United player to lose his life during the war.

Parts of Revill’s life have been a mystery to even such eminent writers as Sheffield United’s historian, Denis Clarebrough, and statistician, Andrew Kirkham, who between them have authored many of the most authoritative historical records of the club, but the acquisition of Revill’s military records has facilitated the filling in of some of the gaps. Previously, not even the Commonwealth War Graves Commission had been able to furnish his date of birth, and neither has his middle name been published before.

Clarebrough and Kirkham’s book ‘Sheffield United Football Club Who’s Who’ gives brief details about Revill’s footballing career. Spotted by United legend Ernest ‘Nudger’ Needham playing for Derbyshire village team Tibshelf, he was signed by the Blades in 1910. Born in Sutton in Ashfield in north Nottinghamshire, he had previously played for local club Sutton Junction. He made his debut for United in a 0-0 draw away to Woolwich Arsenal on January 16, 1910. Revill was mainly a left winger, though he occasionally deputised on the right for absent colleagues, but he found his opportunities limited by the more consistent Bob Evans, who unusually played international football for both Wales and England.

Revill was described as having a powerful shot but his crosses could be too strong and were not as measured as those of Evans, who was always first choice (when fit) during United’s cup winning season, in which Revill played just eleven times. Revill was said to be one of the fastest wingers in the game, strangely dubbed by United supporters ‘old aeroplane legs’. He once told an opponent: ‘I’ve been greased all over today and you’ll never catch me. I’ll give you the biggest doing of your life.’

His final appearance as a professional came exactly five years after his debut, in a 2-0 win over West Bromwich Albion on January 16, 1915, and he ended his United career with 68 appearances and four goals. Football continued on an amateur regional basis from 1915, with Revill playing three more times for United and making guest appearances for Chesterfield Town, Sutton Town and New Hucknall Colliery. But with the war in stalemate, in early 1916 he signed up to do what he could to help his country. In doing so he was forced to leave behind his wife of only a few months.

Jimmy married Olive Shore in the Mansfield district on November 6, 1915. Four years earlier, at the time of the 1911 Census, Jimmy, aged nineteen, lived in a five-room private house at No.27 Morley Street, Sutton in Ashfield, Nottinghamshire. Also living there were his father Frederick (aged 40), mother Hannah, and younger siblings Hannah (15), Lily (13), Frederick (11), Minnie (9), Ernest (5) and Lloyd (one month). Frederick senior was a ‘coalminer holer’, Jimmy’s occupation was given as ‘footballer – Sheffield United’ and the only other member of the family working was daughter Hannah, who was a ‘hosiery maker’, though Lily was described as ‘worker – at home’.

Intriguingly, the Census form was filled in by Jimmy’s mother Hannah, who named her place of birth as Stoneyford, Derbyshire. It was unusual for a woman to complete such an official form, so perhaps Jimmy’s father was illiterate. That is just supposition. Hannah recorded her age as 28, which suggests she was not the mother of some of the children, but the age must be incorrect. Marriage records show that she and Frederick married in the March quarter of 1891, so she must have been 38, not 28, in April 1911, and therefore married when she was still a teenager.

Jimmy Revill’s army enlistment form (Army Form B.2512) reveals that he joined up on February 16, 1916. On that day he gave his age as 24 years 247 days, which equates to a date of birth of June 14, 1891. If his declared age was correct (it was not unknown for recruits to fabricate their age), his mother Hannah, just eighteen, was pregnant when she married. Jimmy enlisted for what was described as ‘Short Service (For the Duration of the War, with the Colours and in the Army Reserve)’ joining the Royal Engineers, and was given the service number 108670. At this time Jimmy gave his address as No.11 Charnwood Street, Sutton in Ashfield.

Army Form B.2512 asked whether Jimmy was a British subject. He was. He listed his ‘trade or calling’ as ‘bricklayer’, with the words ‘desires to follow his trade’ added by hand by another. Jimmy had not previously served, and he said he was willing to be vaccinated or re-vaccinated. Asked whether he received a notice explaining his enlistment, whether he understood its meaning and who gave it to him, Jimmy replied ‘yes’ and ‘Sergeant Carsley, Corps R.E.’

The next question on the enlistment form asked: Are you willing to serve upon the following conditions, provided His Majesty should so require your services?

‘For the duration of the War, at the end of which you will be discharged with all convenient speed. You will be required to serve for one day with the Colours and the remainder of the period in the Army Reserve, in accordance with the provisions of the Royal Warrant, dated 20th Oct,. 1915, until such time as you may be called up by order of the Army Council. If employed with Hospitals, depots of Mounted Units, or as a Clerk, etc., you may be retained after the termination of hostilities until your services can be spared, but such retention shall in no case exceed six months.’

Jimmy said yes, and signed the confirmation that ‘I, James William Revill, do solemnly declare that the above answers made by me to the above questions are true, and that I am willing to fulfill the engagements made.’ His answers were witnessed by Sergeant J. Carsley. Jimmy then took the oath:

I, James William Revill, swear by Almighty God, that I will be faithful and bear true Allegiance to His Majesty King George the Fifth, His Heirs and Successors, and that I will, as in duty bound, honestly and faithfully defend His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, in Person, Crown and dignity against all enemies, and will observe and obey all orders of His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, and of the Generals and Officers set over me. So help me God.

The Attesting Officer, G. G. Bouser, then signed and dated the form to affirm that:

The above-named Recruit was cautioned by me that if he made any false answer to any of the above questions he would be liable to be punished as provided by the Army Act. The above questions were then read to the Recruit in my presence. I have taken care that he understands each question, and that his answer to each question has been duly entered as replied to, and the said Recruit has made and signed the declaration and taken the oath before me.

Finally, the Approving Officer added the following confirmation:

I certify that this Attestation of the above-named Recruit is correct, and properly filled up, and that the required forms appear to have been complied with. I accordingly approve and appoint him to the Royal Engineers.

On a supplementary sheet entitled ‘Descriptive Report on Enlistment’ Jimmy stated that his next of kin was his wife, Olive Revill, of No.11 Charnwood Street, Sutton in Ashfield, Notts, but this address was crossed out and replaced by ‘Rothsey’, Alfreton Road, in the same town. This particular form was updated to record the recruit’s career and life, for a later addition was the name of a son, Jack, born on August 1, 1916.

After acceptance into the army Jimmy had to undergo a medical examination, the details of which were recorded on Army Form B.178. His height was measured as 5 feet 6-5/8 inches and his weight as 165 lbs. The girth of his chest when fully expanded measured 36-1/2 inches, with a range of expansion of 2-1/2 inches. Jimmy’s physical development was described as ‘Very Good’, and he had three vaccination marks, all administered in infancy, on his left arm. Alongside the question ‘Marks indicating congenital peculiarities or previous disease’ the examining doctor wrote: ‘Op. scar on lumber region for excision of “birth mark”.’ He then added a question mark as if to state that he did not fully understand Jimmy’s explanation of the scar.

The new recruit exhibited nothing that fitted the description ‘Slight defects but not sufficient to cause rejection’ and was classed ‘Fit for service in field at home or abroad’, a phrase written in the doctor’s own hand. The doctor then signed the form ‘C. Cooke MB BS, Lt RMC T’. Jimmy Revill was now a member of His Majesty’s forces. He was not required for immediate service as he first had to undergo military training, and he remained in Britain until August. He was called up for General Service on March 20, 1916, joining the Royal Engineers in the rank of Sapper.

One of his first tasks was to collect his equipment, and he was required to tick in red the items he received from the Quarter-Master on a list entitled ‘Clothing and Necessities issued at the R.E. Clothing Store’. He had his hands full with the following: Greatcoat, drab 1. Boots, ankle pairs 2. Cap, s.d. 1. Drawers pairs 2. Jackets, s.d. 2. Putties pair 1. Shoes, canvas pair 1. Trousers, s.d. 2. Waistcoat, Cardigan 1. Badge, cap 1. Bag, kit 1. Blacking, tin 1. Braces, pair 1. Brass, button 1. Brush – Blacking 1. Brush – Brass 1. Brush – Clothes 1. Brush – Hair 1. Brush – Polishing 1. Brush – Shaving 1. Brush – Tooth 1. Cap comforter 1. Comb 1. Disc, identity & cord 1. Fork 1. Holdall 1. Housewife 1. Knife – Table 1. Laces, leather, pair (spare) 1. Lanyard 1. Shirts 3. Socks, pairs 3. Spoon 1. Titles, R.E., G.M. 4. Towels 2.

Jimmy was mobilised on March 22, and went to the regimental training centre at Deganwy, Gwynnedd, North Wales, on April 6. Four months later he was considered ready for active service and was sent to join the British Expeditionary Force in France on August 21. Then, on September 13 he was assigned to the 104th Field Company of the Royal Engineers, which formed part of the Army’s 24th Division, at this time stationed at Ginchy. Jimmy must have been a model soldier (or Sapper), as his record (Army Form B.121 – Squadron, Troop, Battery and Company Conduct Sheet) shows no instances of misconduct or punishment. Accordingly he was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal on March 2, 1917.

By the following month the 24th Division, and with it the 104th Field Company, had been transferred to Vimy and took part in what was known as the Battle of Arras, an offensive that commenced on April 9. Jimmy Revill was not to see the end of the first morning. At 10pm that evening the Royal Engineers Records Office at Chatham received a telegram from the War Office, which read:

To:- Attest Chatham

9.4.17

C2 Cas P.56276 O.C.

33 Casualty Clearing Station France

Telegraph 9th April, Dangerously wounded 102670 Private J. R. Reville, R.E. 104 Company

Proelicas

The wording is self-explanatory (but the name and rank are incorrect), although the final word ‘Proelicas’ needs some explanation. The ‘Great War Forum’ reveals its meaning: ‘Proelicas’ was a telegraphic address for the War Office department dealing with casualties. It is from the Latin ‘proelium’, meaning battle, and the abbreviation ‘cas’, meaning casualty. A telegram was consequently dispatched from Chatham to Jimmy’s next-of-kin, his wife Olive:

To:- Revill

Rothsey

Alfreton Road

Sutton-in-Ashfield

Nottingham

Regret to inform you Officer Commanding 33 Casualty Clearing Station France telegraphs 108670 J. W. Revill R.E. dangerously wounded

Regret permission to visit cannot be granted.

Colonel in charge WCW Captn for Colonel i/c R.E. Records

Royal Engineers Records

Brompton Barracks

Chatham

One can only imagine Olive’s distress and worry as on the morning of April 12 she walked to her local post office to send a telegram to the Royal Engineers, Chatham, asking about her husband’s injuries:

Office of Origin: Sutton in Ashfield

Handed in at 11.17am

Received here at 11.51am

Chatham 12 Ap 17

To:- Colonel in Charge Royal Engrs Records Chatham

Could you give me further information concerning 108670 J. W. Revill condition and name the Hospital.

Mrs O. Revill

Rothsey

Alfreton Road

Sutton in Ashfield

Unfortunately Olive was too late. The previous day the Royal Engineers Records Office had received another telegram from the War Office:

Office of Origin: OHMS Kingsway

Handed in at 8.00pm

Received here at 8.45pm

Chatham 11 Ap 17

To:- Attest Chatham

C2 cas P 56604 O/C

33 cas clg stn France reports 9th April. Died 8.40 am 9th April 108670 L/Cpl J. W. Revill R.E. 104 Fld Coy G.S.W. Back perf Chest injury to spine Proelicas

The shorthand informs in matter-of-fact manner that Lance Corporal J. W. Revill, Service No. 108670, of 104th Field Company Royal Engineers, received a gunshot wound to the back, which perforated his chest and injured his spine. He died at 33rd Casualty Clearing Station, located at Bethune, northern France, at 8.40am on April 9, 1917. No reply was made to Olive’s request for more information about her husband’s injuries. Instead, a hand-written note on her telegram recorded: ‘No action taken wife previously dispatched reporting death’. The fateful telegram to Olive read:

To:- Revill

Rothsey

Alfreton Road

Sutton-in-Ashfield

Nottingham

Regret to inform you Officer Commanding 33rd Casualty Clearing Station France reports April 9th 108670 James Revill R.E. died April 9th gunshot wound back penetrating chest and injury to spine.

Colonel in charge Royal Engineers Records

Brompton Barracks

Chatham

12/4/17

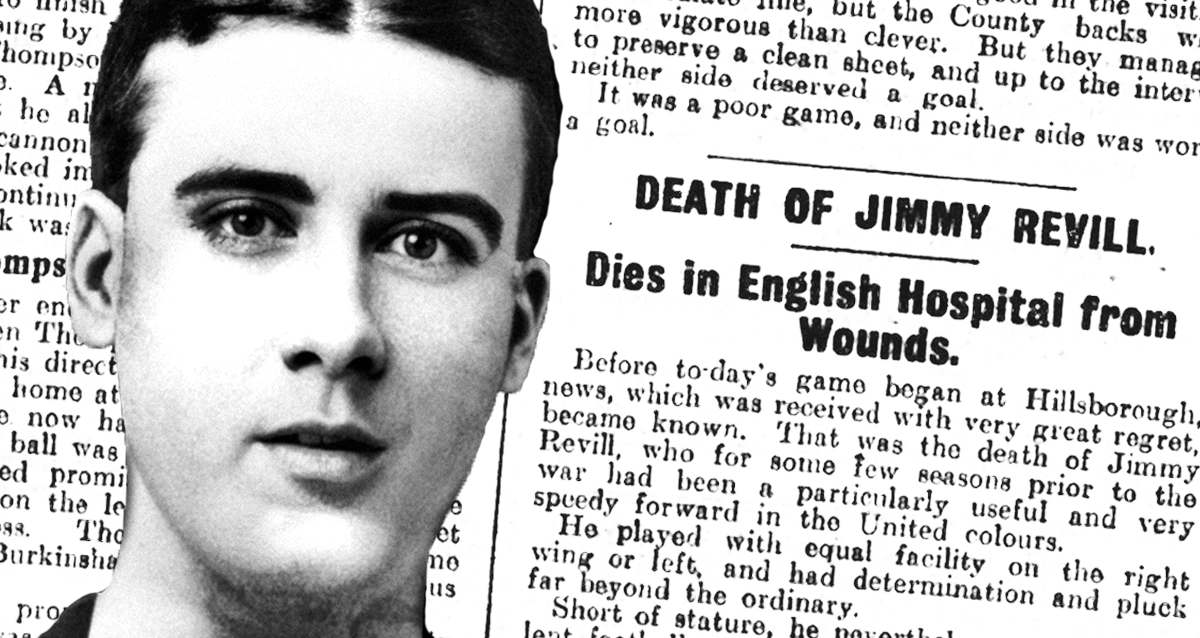

News of Jimmy’s death reached the local press a week after it occurred, and was reported in both the Sheffield Daily Telegraph and the Sheffield Independent on April 16, 1917. The Telegraph wrote:

News was received in Sheffield on Saturday, with very great and general regret, of the death of Jimmy Revill, who for some seasons prior to the war had been a particularly useful and very speedy forward in the United colours. He played with equal facility on the right wing or left, and had determination and pluck far beyond the ordinary. Short of stature, he nevertheless was an excellent footballer, and very popular. He has died in an English hospital as the result of wounds sustained at the front, and which necessitated the amputation of an arm and a leg. Revill was married, and joined up some fifteen or eighteen months ago, and had seen quite a lot of fighting.

The Independent’s report followed similar lines, but made no mention of the nature of Revill’s injuries or the location of the hospital in which he died. It is obvious today that the Telegraph was mistaken, or misinterpreted what they had been told, as Revill died in a casualty station in France and his wounds – caused by a single, but catastrophic, bullet – were not as described in the report. However, the Telegraph can be forgiven its error because of the restrictions on the dissemination of information that were in force at the time.

It cannot be known how Jimmy’s wife Olive took the news of his death. Like hundred of thousands of other young wives, she would never learn the exact circumstances that caused her husband to be killed in action, and she had to quickly come to terms with life as a widow. One of the practicalities she would not have to organise was a funeral, as her husband was buried locally, in accordance with military practice, at Bethune Town cemetery, Pas de Calais, 29 kilometres north of Arras. Eventually, the cemetery would become the last resting place of 3,003 other First World War victims (eleven of them unidentified). Jimmy’s grave reference from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website is shown below:

But the Royal Engineers did not forget about Olive Revill, for she was still due a portion of her husband’s pay. Captain W. C. Wattem, acting on behalf of the Officer in Charge of Records for the Royal Engineers Chatham Station, sent a memo to his colleague the Regimental Paymaster requesting that he ‘report on the back of this form the full Christian name, address and relationship of the person, if any, drawing allotment of pay or separation allowance in respect of No.108670 Sapper James Revill, Royal Engineers’. The Paymaster replied with the required details, and stated that the ‘Continuing’ rates of allowance to be paid to Olive were 16/- Separation Allowance and 7/- Allotment of Pay. Later correspondence, on July 27, 1917 corrected Jimmy’s rank from Sapper to Lance Corporal.

Army Form B.104-76 was then sent to Olive, which informed her that in order to receive her payments she needed to supply to the Records Office her marriage certificate and her child’s birth certificate, with the form countersigned by a Magistrate, a Minister of Religion, a Medical Practitioner a Postmaster or a Police Officer not under the rank of Sergeant. The formalities of pay completed, attention could now turn to Jimmy’s personal possessions and medals. The War Office used Form 118A to instruct the Royal Engineers Record Office to return said possessions and medals to Olive.

In September 1917 Olive wrote, in her own neat and tidy handwriting, to the Royal Engineers Records Office informing them of her change of address, to No.10 Doreen Drive, Alfreton Road, Sutton in Ashfield. Neither did Sheffield United forget about Olive Revill. On January 12, 1918 the club staged a benefit match for her against a team representing Hadfield’s, the Sheffield steel and munitions manufacturing company. The match resulted in a 3-3 draw, with United’s goals coming from Harry Johnson, Ben Shearman and Wally Masterman, who had played in the FA Cup final almost three years earlier. Shearman was a guest player whose main club was West Bromwich Albion. An attendance of around 3,000 raised £130 for Olive, a sum worth over £7,500 today.

The final pieces of correspondence in Jimmy Revill’s World War One military records came over three years later, in the summer of 1921. The first was a letter from Captain A. W. Tebbutt of the Royal Engineers Records Office, who requested from the Secretary, Pensions Issue Office, Widows and Dependants Branch, Regents Park, N.W.1, the present address of the widow or dependants of Lance Corporal J. W. Revill, R.E. ‘to enable me to issue forms in connection with the Imperial War Graves Commission’. The reply, dated July 28, 1921, informed that Olive Revill had re-married on January 8 that year, to H. C. Hildreth, and that her new address was No.57 Wood Street, Holmwood, Chesterfield.

It was only in September 1921 that Olive received his war medals, namely the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. She duly signed the accompanying form to acknowledge receipt. The passing of Jimmy Revill’s war medals to his widow brought a close to a sad chapter in her life, one that was shared by so many other young women of the period. Unlike some, Olive managed to find a new love and although she would never forget about her first husband, the father of her son Jack, she had finally come to terms with his loss and settled down to a new life with her new husband.

By Matthew Bell

Author of ‘Red, White and Khaki: The Story of the Only Wartime FA Cup Final’