THE STORY OF THE 1914/15 SEASON

Great Britain’s involvement in what would later become known as the First World War began at 11pm on 4 August 1914. Having received unsatisfactory response to its ultimatum demanding the immediate withdrawal of German troops from neutral Belgium, the Foreign Office announced to the country that Britain had commenced hostilities with Imperial Germany.

It was the beginning of four years of conflict that would eventually claim the lives of almost one million soldiers, sailors and airmen from Britain and her dominions. More than twice that number would be wounded, taken prisoner or go missing. It was loss on an unprecedented scale and an experience so traumatic that it would cast a shadow across much of the following century.

Yet the initial decision to go to war was generally well received. There was a surge of patriotism in the days that followed the declaration, with crowds gathering at locations of national importance such as Buckingham Palace, Downing Street and Trafalgar Square. Elsewhere, officials and volunteers alike launched into the incredible task of mobilising the country for war.

Despite the obvious challenges that faced the country, much of its population were still able to go about their daily lives with some degree of normality. Music halls, theatres and cinemas remained open, while organised sport retained huge importance for many – not least professional football which was just weeks away from the start of a new season. For significant sections of society, it was still very much “business as usual”.

On 7 August 1914, Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener, newly-appointed Secretary of State for War, sent out an appeal for the first 100,000 men to fill the ranks of the new “citizen” army that he had demanded be raised, and volunteers began flooding into the many recruitment halls that had been established around the country. The initial response was good and by the end of September, over 750,000 men had enlisted to serve in what would become known as Kitchener’s “new army”.

Elsewhere, most football clubs were going about their daily business much as always. Early inconveniences, not least at Manchester City and Newcastle United who were among those to have their grounds temporarily requisitioned by the Army, had been addressed and players and staff members were now arriving back after the summer break to begin pre-season training in earnest.

While no official announcement on the future of the new season had been made, representatives from the Football Association (FA), including its chairman Charles Clegg and secretary Frederick Wall, maintained things should proceed as scheduled. They argued continuance of the full league programme would not only help maintain morale, but would also present excellent opportunities to boost recruitment and raise much-needed money for the various war relief funds. It was a belief also held by both the Football League and Southern League.

Supporters also highlighted the fact that a great many professional players were married men with young families, who were not yet being asked to volunteer, and would have no other means of income should football be stopped. While most were unlikely to admit it at that time, the economic ramifications of suspending the season remained of primary concern for many involved in professional football, both at club and governmental level.

Controversy and Condemnation

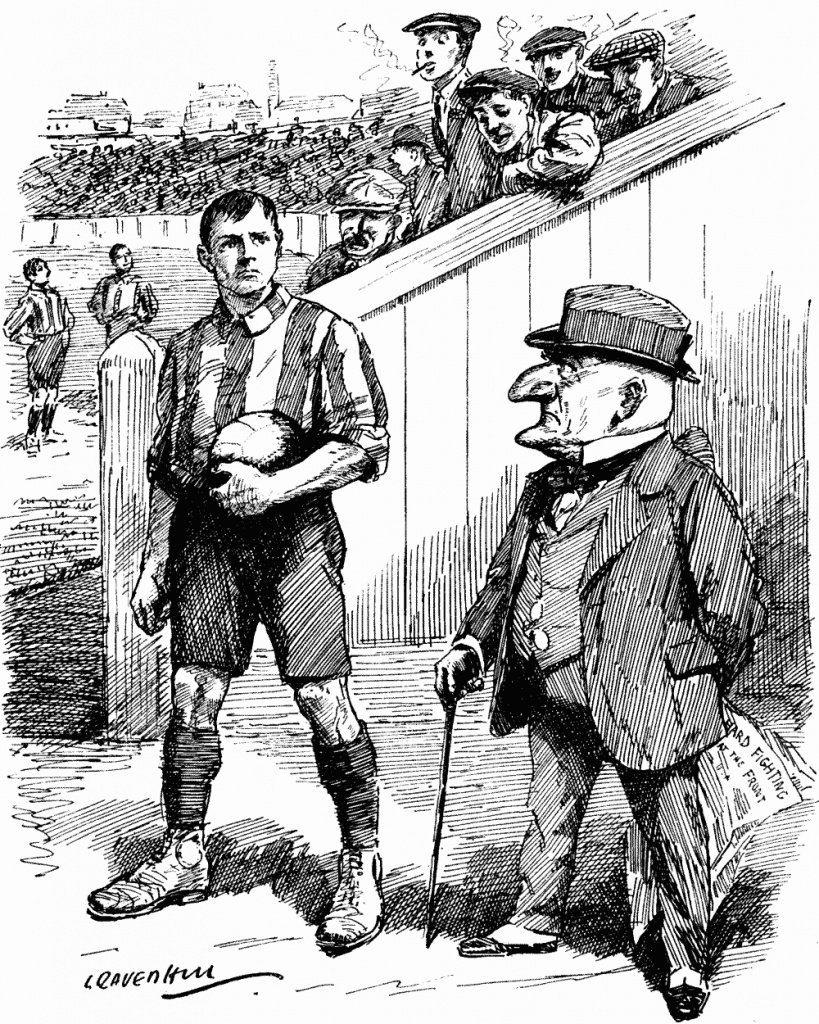

The desire to press on with the league campaign was soon met with condemnation from a number of highly vocal critics and was to set the tone for one of the most controversial football seasons in history. High profile opponents included the likes of W.G. Grace, who had also been highly critical of the decision not to halt the county cricket season, and respected East End social reformer and temperance advocate, Frederick Nicholas Charrington, who was to soon single out West Ham United for particular condemnation.

Critics argued that many other sports had already cancelled competition for the duration and had, in addition, also made substantial contributions in manpower to the war effort. This was especially true of the country’s amateur sports, including amateur football, who possessed a significant number of army reservists and territorial soldiers within their ranks. For professional football to continue “playing the game” while young men were dying on the battlefields of France and Belgium was seen as morally reprehensible by football’s opponents.

Of those sports that had taken action, the Rugby Football Union (RFU) were amongst the most willing to halt competition and actively encourage members to offer themselves for enlistment. The preserve of the upper and middle classes, the RFU had acted swiftly when war was declared and immediately cancelled both international and county matches. This decision was quickly followed by its clubs who had seen a significant number of their players enlist in the first weeks of the war. In addition to the RFU, the Amateur Football Association (AFA) had also suspended its competitive programme soon after the outbreak of hostilities.

For some, however, the vehement criticism of professional football was seen as nothing more than an extension of the class divide that was embedded in English society at that time. Proponents of the amateur game had been horrified by the introduction of professionalism in 1885 and decades of unrest had followed. In 1906, the AFA broke away from the FA and remained independent until 1913 when they returned to the fold – albeit with some unease. Many now believed the war had presented a perfect opportunity for old scores to be settled.

On 22 August 1914, the day before the British Army fought its first major action of the war at Mons, clubs up and down the country took part in a series of matches to raise money for the Prince of Wales’ National Relief Fund. By the end of August, football had raised more than £7,000 for the war effort – considerably more than any other sport. It was a remarkable effort, yet it did little to dampen criticism. On 31 August, committees from the Football League, Southern League and the Football Association met at their respective London headquarters to discuss the increasingly difficult situation that faced the game.

On 22 August 1914, the day before the British Army fought its first major action of the war at Mons, clubs up and down the country took part in a series of matches to raise money for the Prince of Wales’ National Relief Fund. By the end of August, football had raised more than £7,000 for the war effort – considerably more than any other sport. It was a remarkable effort, yet it did little to dampen criticism. On 31 August, committees from the Football League, Southern League and the Football Association met at their respective London headquarters to discuss the increasingly difficult situation that faced the game.

For those calling for an immediate halt to competition, the meetings were to prove disappointing. Both the Football and Southern League announced that the season would go ahead as planned, although it was recommended that clubs provide basic military drill and shooting practice for players. The FA meanwhile, urged clubs to release staff from contracts so they could enlist without fear of legal action if they so wished. In addition, they advised clubs to place their grounds at the disposal of the War Office on non-match days and also asked them to permit prominent figures to address crowds in an effort to stimulate recruitment.

The Season Begins

On 2 September 1914, one day after the first games of the new season had taken place, it was announced that the County Cricket Championship was to be cancelled with immediate effect. Although there were just three fixtures left to play, the decision to halt the cricket season was seen as significant and gave hope that football would now be forced to follow suit.

There was to be no backtrack, however, and one week later every club had completed its first round of fixtures. Opponents were outraged and a number of scathing attacks were launched in the national press. Dr Thomas Fry, Deacon of Lincoln and a former public school headmaster, was among the most vociferous and went so far as to suggest that the desire to continue was down to nothing more than financial greed. He also demanded that restrictions be put in place that would prohibit any spectator under the age of 40 from entering a football ground. Frederick Charrington meanwhile, maintained his vehement opposition to the game and even sent a telegram to King George V in which he suggested the monarch withdraw his royal patronage from the FA.

On 4 September 1914, and with pressure intensifying, the FA announced that it had placed itself at the full disposal of the War Office and began efforts to increase match-day recruitment. The FA also asked the War Office for official sanction to continue the season, but stated they were ready to stop it with immediate effect should the government believe this was the best course of action. Frustratingly for the FA, they were to receive neither sanction to continue nor recommendation to stop.

While the arguments rumbled on, it soon became clear that the significant drop in attendance levels, and thus gate receipts, at the majority of grounds were edging some clubs closer to financial ruin. In the Second Division, season ticket sales were down from an average of £516 to just £177, while it was estimated gate receipts would drop from £326,017 during the 1913/14 season to £210,620 by the end of the current campaign. It was warned the second tier would soon collapse under these dire financial conditions.

Brotherhood and Burden

In an effort to address the increasingly precarious situation, the country’s best-paid players were encouraged to take pay cuts in a spirit of “brotherhood”. Those on the maximum wage of £5-per-week subsequently agreed to a 15% reduction, while players earning less than £3 took a 5% cut. The amounts saved, estimated to be around £300, were then paid into a relief fund and used to help clubs struggling to stay afloat. On 9 October, the Football League held an emergency meeting in Manchester and approved another set of contingency plans, which would see clubs also contribute 2.5% of their gross gate receipts to the fund.

As the financial burden on clubs grew, so too did the denigration of football as losses continued to mount on the Western Front. The pre-war BEF had been all-but destroyed as it clung on desperately against repeated German attacks around the town of Ypres in October and November, while the mammoth logistical effort needed to maintain supplies for the war effort was creating a huge strain on the country’s infrastructure.

Under these circumstances many questioned the morality of those promoting the continuance of football and calls were made in the Houses of Parliament for the the prime minister to introduce legislation to stop the season forthwith. In late November, football received a further significant blow when it was announced that the popular press would no longer publish football-related content other than results – and only then in specific sports newspapers.

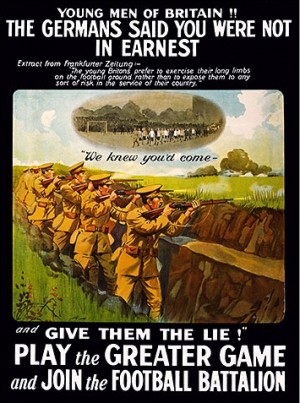

As the situation deteriorated, the War Office held further discussions with the FA during which a call was made to end both international matches, which was agreed to, and the FA Cup, which was dismissed. It was also suggested that a specially designated footballers’ unit be formed, similar to the ‘Pals’ s that had proved so popular during Kitchener’s initial recruitment drive. The proposal was generally well-received, with many pointing to the success of a similar unit in Scotland, into which Sir George McCrae had recruited players, staff, match officials and football supporters.

By early December, it was clear football’s position had become untenable and a decision was finally taken to convene a meeting to discuss the raising of a new football . Letters were sent to each of the 11 professional clubs in the London area inviting them to attend talks on 8 December. Representatives from the Football League, Southern League and Football Association would also be in attendance, as would the chief army recruitment officer for London, Captain Thomas Whiffen. The meeting was to be chaired by William Joynson-Hicks MP, who had been tasked with raising the by the War Office.

Following productive preliminary talks, a further meeting was held at Fulham Town Hall on 15 December 1914, during which the 17th (Service) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, better known as the “Footballers’ Battalion” was officially raised by Joynson-Hicks after 35 professional players had volunteered to become its first recruits.

In mid-January, it was reported that the had attracted almost half of the 1,350 volunteers needed to bring it up to full strength. By the end of March, it was complete and had already undergone some weeks of military training. Critically for the FA and both the Football League and Southern League, each footballer that enlisted would be permitted to turn out for both their club whenever possible.

Across the channel, there had been more bitter fighting and yet more casualties. The Germans had flung themselves into another attack around the town of Ypres and while the Allies hung on, they had sustained huge casualties. Significantly, the battle marked the first mass use of poison gas, while German forces had also employed the much-feared flamethrowers for the first time.

On 25 April 1915, Allied troops were to also land on the beaches of Gallipoli as they sought to knock Turkey out of the war and open a route through the Dardanelles. Similarly to the campaign on the Western Front, however, stalemate soon ensued as Turkish troops tried to push the allies off the peninsula. By the time the ill-conceived campaign was brought to a close in January 1916, the British Army alone had lost more than 120,000 men.

The End

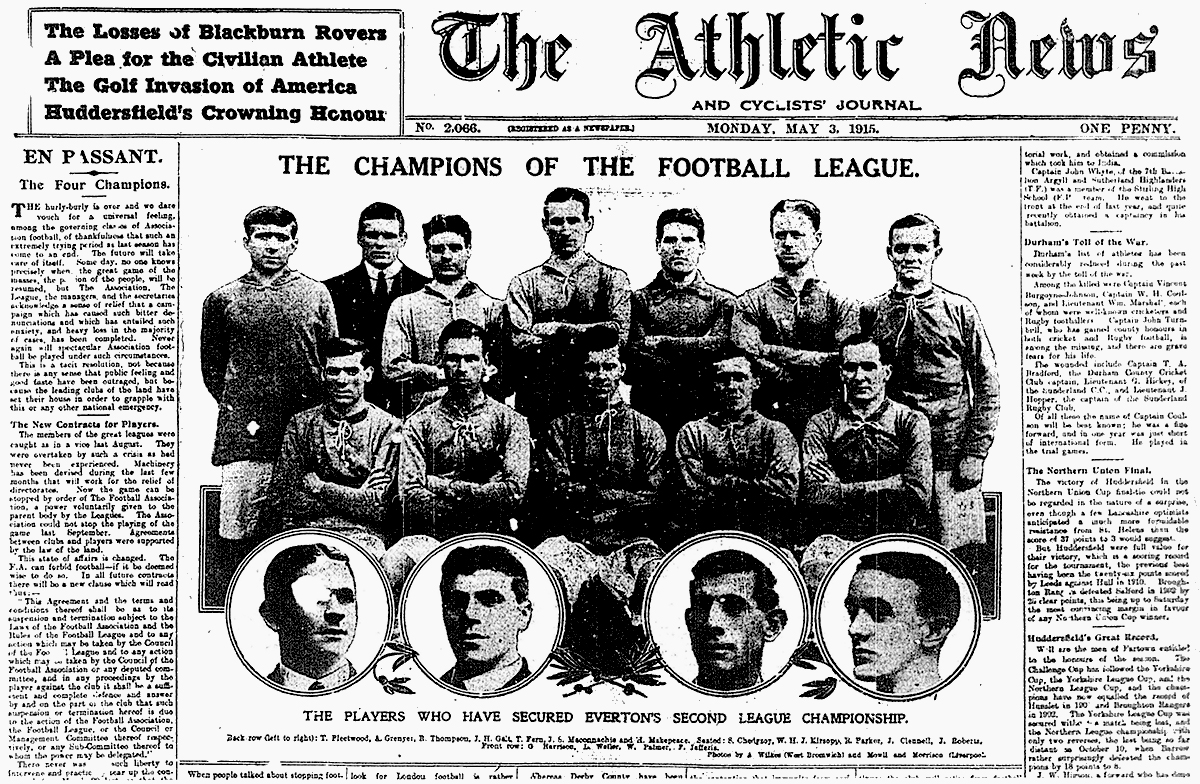

The 1914/15 league campaign finally reached its conclusion at the end of April 1915, when Everton were crowned First Division champions for just the second time in their history. All that remained was the FA Cup Final, which was played out at Old Trafford on 29 April 1915 between Sheffield United and Chelsea. Soon dubbed the “Khaki Cup Final” due to the overwhelming number of servicemen in attendance, the game was won by the side from South Yorkshire after a comfortable 3-0 triumph.

Just weeks after the match, both the Football League and Southern League announced they were to suspend their league programmes for the duration of the war and would, instead, run unofficial regional competitions that would provide little disruption to the war effort. The FA Cup was also cancelled until the end of hostilities and regulations were brought into effect to prohibit the payment of any player, in turn bringing to a close one of the most controversial and challenging periods in the history of the English game.

By the time World War One ended on 11 November 1918, many of those who took part in that tumultuous season were either dead or had been forced to retire from the game due to injuries received on active service. For those who did return to resume footballing careers, many would harbour resentment over the criticism they had been subjected to while the 1914/15 season rumbled on. Faced with a similar situation at the start of the Second World War in September 1939, those running the English game acted far more decisively and immediately cancelled the full league programme.